Why is personal change so difficult? Why do we so often get stuck in our habitual behaviours and engage in pain avoidance and quick-fix solutions, rather than pushing through discomfort to move towards our values and a more meaningful life?

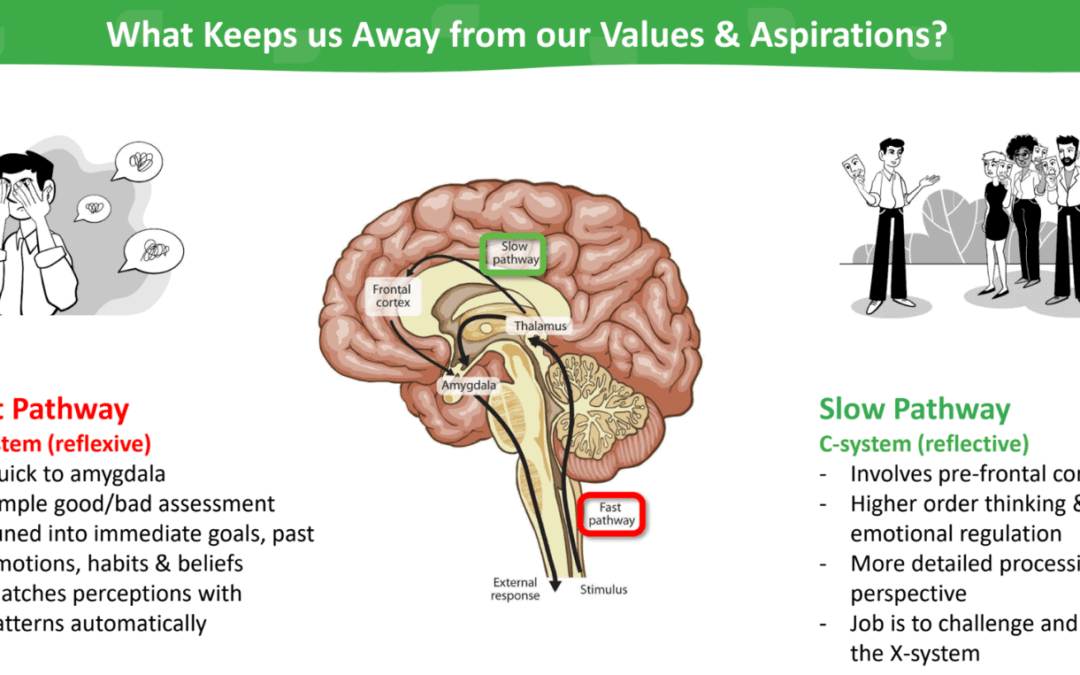

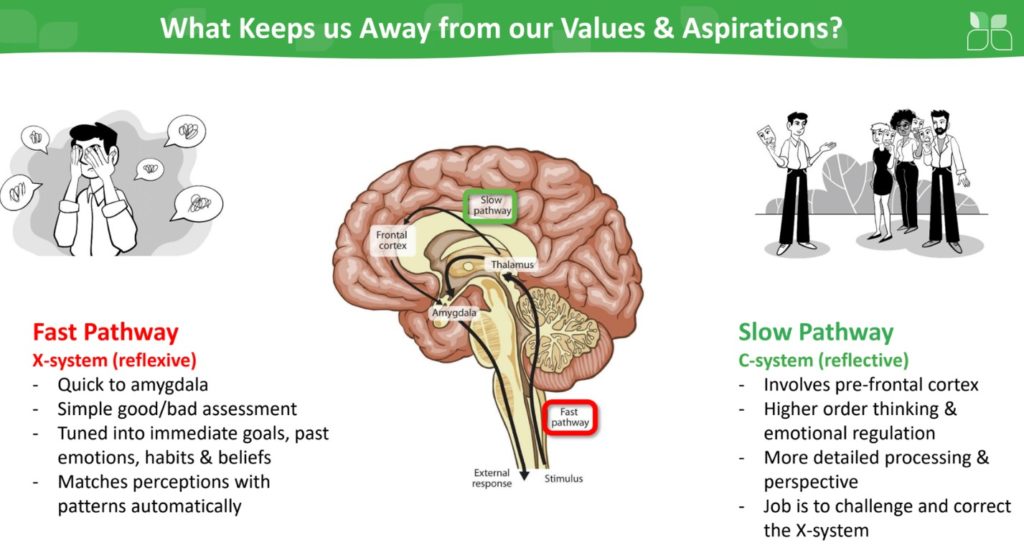

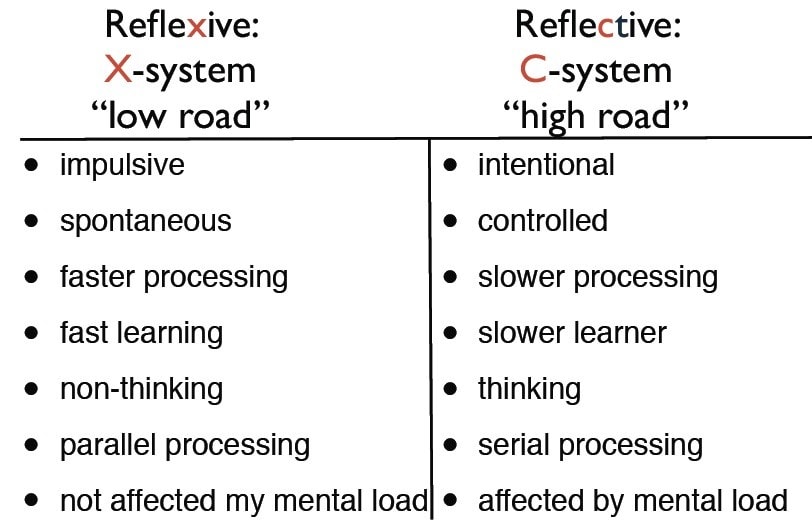

Research by neuroscientists Joseph LeDoux and Matthew Lieberman sheds light on these questions. According to LeDoux, our brain has two pathways through which the amygdala’s fear responses can be triggered: a fast ‘low road’ from the thalamus to the amygdala, and a slower ‘high road’ that passes from the thalamus to the prefrontal cortex and only then to the amygdala (figure 1.2). He explains that these two systems don’t always reach the same conclusions.

Lieberman refers to these two pathways as the ‘X-System’, which is reactive (a fast pathway), and the ‘C-System’, which is reflective (a slow pathway), meaning it gives us time to reflect and make more conscious choices (figure 1.2).

This fast brain is a product of evolution and is part of our mammalian brain. It has served us well over the years, enabling us to escape from predators and avoid social rejection, both of which could make the difference between life and death. The brain has essentially not changed much since those hunter-gatherer days and is still wired the same way. According to the National Science Foundation, the average person has between 12 000 and 60 000 thoughts per day. Of those, 95 per cent are repetitive thoughts and 80 per cent are negative, designed to keep us safe from potential predators and risks.2

The fast brain thus engages the parts of the brain that act spontaneously and impulsively (our emotional centres). The slow brain, on the other hand, is linked to our more recent brain development that differentiates us from other mammals. These more evolved neural structures, such as the prefrontal cortex and its executive functions, engage parts of the brain that enable us to act with intention and awareness before our fast-brain reflex response takes over. This system also helps regulate the emotional fight, flight or freeze reactivity of the fast brain.

What keeps us away from our values and aspirations

When the reactive fast brain is triggered by something we perceive as a threat, the slower brain is suppressed as hormones surge through our bloodstream and neurotransmitters flood our brain. As a result, we respond impulsively and lose our ability for self-awareness and self-regulation. The reactive parts of our brain take over and we become defensive. We don’t see things objectively. We don’t listen well to others because our brain is consumed with defending against a threat. In the modern world, we often perceive interactions as threats, when the only thing they really threaten is our self-image.

The reactive fast brain is focused on past emotional memories, short-term goals, habits and beliefs. When operating from the fast brain, our responses are emotional, conditioned and habitual. The brain matches perceptions with patterns automatically, which shuts down curiosity, learning and growth. If we don’t cultivate self-awareness, it’s the unconscious mind or fast brain that’s really in charge.

The slow brain, on the other hand, gives us the ability to become the observer, broaden our perspective, think more logically and creatively, see things with more clarity and wisdom, and ultimately choose new behaviours. The job of the slow brain is to challenge and correct the fast brain.

Mastering personal growth requires that we bring mindfulness to fast-brain reactions, which sabotage our long-term goals, and operate more from the slow brain or prefrontal cortex in order to move towards our values and goals. To shift from our fast to our slow brain, we need self-awareness and the ability to self-regulate. We can also shift from the fast brain to the slow brain by having clear intentions and deliberately choosing our values and responses, rather than being held hostage by quick habitual responses.

When operating from the reactive fast brain, external events trigger our unconscious beliefs, which then trigger unconscious, conditioned actions and behaviour. Overcoming these instinctive reactions requires two things: (1) replacing unconscious fears, beliefs and assumptions with presence, awareness and consciously chosen values (internal work); and (2) aligning our thoughts and behaviours with our values (actions that support our internal aspirations).

It’s pointless to choose our desired path forward and underlying values without a daily commitment to deliberately cultivating those values in action. As a leader, for example, you will note that your team members don’t experience your aspirations; they experience your behaviour.

Our fast brain seeks to avoid discomfort and to achieve short-term gratification. The mere idea of choosing a behaviour outside our usual repertoire will be unconsciously strongly resisted. We need to bring awareness to this discomfort and consciously choose with our slow brain what is truly best to support our growth, rather than please the ego structure that seeks validation or comfort.

Recent research suggests that our knee-jerk conditioned responses protect our ego structure through our brain’s default mode network (DMN). This neurological structure is responsible not only for protecting our physical wellbeing by scanning the environment and sending information to our limbic system (fast brain), but also for protecting our emotional wellbeing. This automatic reaction seeks not expansion or innovation, but protection.

Personal growth is all about moving from fast-brain reactivity to slow-brain proactivity. It’s about defining what you really want to further develop in your life and/or your leadership, then cultivating that through clear intent and committed action.