For the past 20 years I have worked with leaders and organisations to help create positive change in both. In my work, I differentiate between horizontal development and vertical growth, and I focus primarily on vertical growth.

Horizontal development means developing the skills and gaining the knowledge you need to work in the organisation to get your job done efficiently, effectively and safely. Vertical development is much deeper. It means developing the ability to change how you perceive and value your inner and outer world (mindset), then building the self-regulating awareness to support the development of new behaviours in a sustainable way aligned with your core values.

We’ve always wondered why some people are clear about following virtuous leadership principles such as honesty, generosity, kindness and curiosity even under pressure, and some people aren’t, and why some people take them seriously and some don’t. Why do some people think they are acting from these virtues when they are not, and why are some people more honest with themselves than others? The obvious answer, of course, is that although they may be highly skilled and competent, incongruent leaders lack vertical growth.

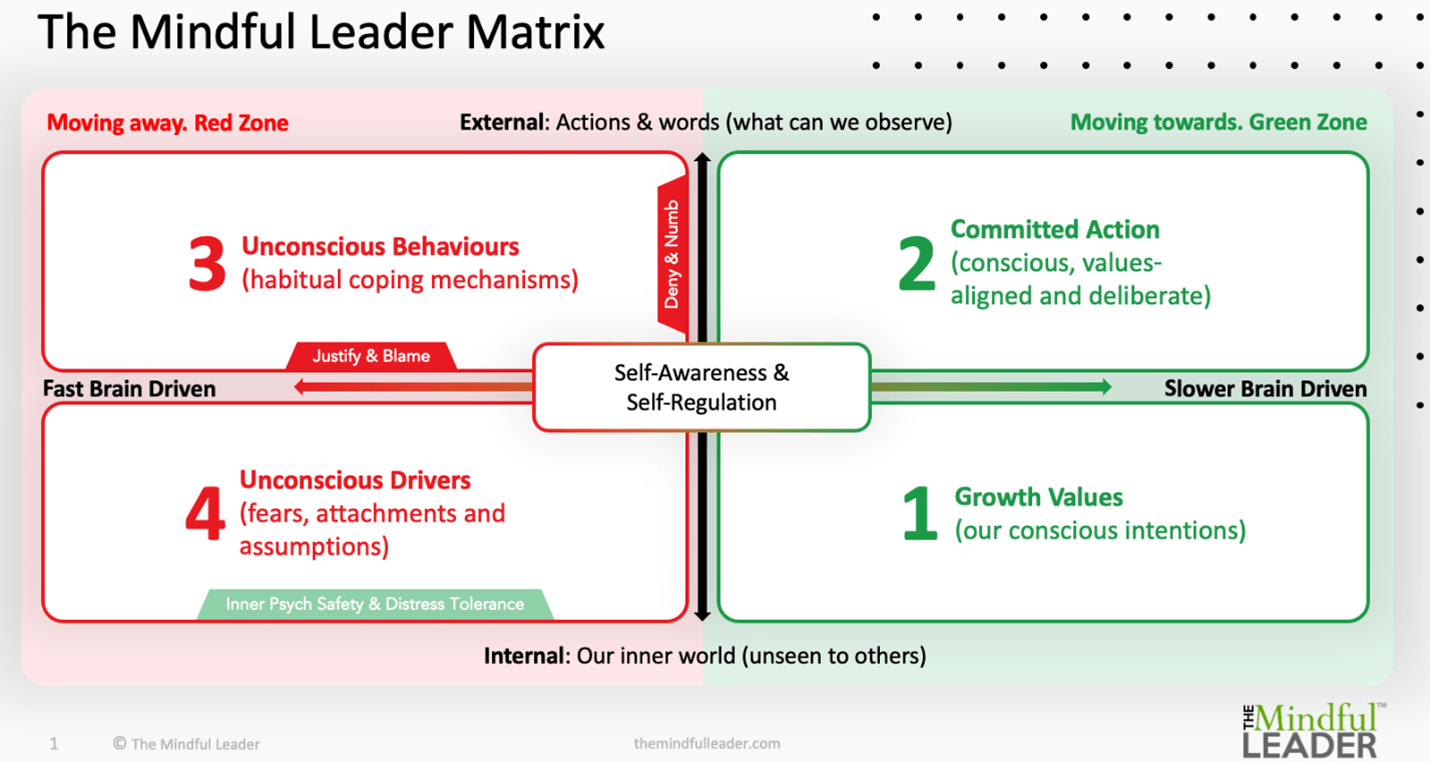

In order to formalize the vertical growth process and make it predictable and sustainable, I developed what I call the Growth Matrix.

The Growth Matrix drew on a variety of key sources, including Steven Hayes’ Acceptance Commitment Therapy (or Training) (ACT), Robert Kegan’s work on Immunity to Change, and the advanced transformational leadership and self-awareness practices we have researched and developed through our work with leaders and organisations around the world.

This new and original formulation of the matrix also allows for culture change and organisational development work. This represents the culmination of 20 years of study, research and practice in the areas of leadership, team and culture development.

How to use the matrix

The horizontal axis shows us moving either towards or away from our growth values and conscious intentions. The zone on the right represents our values, aspirations, purpose and healthy desired behaviours. The zone on the left represents unconscious and conditioned responses, quick-fix solutions, short-term rewards and pain avoidance.

The bottom area of the horizontal axis represents our internal world of feelings and mental models. Inside this area we also find the unconscious values we have adopted from our parents, teachers and society since birth. Our mental models are the framework with which we interpret and perceive the world. They are deeply rooted in our unconscious. While they operate in the present, they are constructed from the past — often the very distant past, as our brain is most plastic in our early years and defines our ego structure for decades to come. These mental models have typically been reinforced at critical stages of our lives; they determine our psychological flexibility and shape our actions.

The less self-awareness we have of our mental models, the more psychological rigidity we will have. This means our thoughts and behaviour can be a little like a repeated recording. We play out similar responses to variable realities. For example, a leader might micromanage others inappropriately as a conditioned response to fear of losing control. In his childhood he may have experienced trauma while having no power or control, then developed a fixed mental model that insisted on always maintaining high levels of control. This may have been useful in extreme circumstances and may have helped him cope with the early trauma, but it leads to a rigid, repeated set of behaviours that become problematic and disconnected from reality in later life.

This is what we mean by rigidity. Our past conditioning is rigid and fixed. The human brain evolved over millions of years to find quick fixes in our early years and to wire that in for future coping needs. The more self-awareness we develop, the greater our psychological flexibility. This opens our mind to increased possibilities. We move away from self-preservation and towards expansion, as we mindfully see our mental models more clearly and can make choices to overcome them. For example, it might be quite appropriate to micromanage in an extreme emergency, and be completely inappropriate to do as a daily leadership practice. The self-aware leader can do both, depending on what is actually needed. In other words, she has developed psychological flexibility.

The top area of the horizontal axis represents our external world: our words, actions and behaviours. Behaviours can be reactive or impulsive when they emerge from what is called our ‘fast brain’, also referred to as our mammalian or limbic brain. Or they can be deliberate and values-based when we are able to self-regulate our emotions with our ‘slow brain’, emerging from our more advanced prefrontal cortex and other cortical areas, and have clarity on what is important to us.

The more we are committed to the right side of the matrix, the easier it is to have agency over the left side, and the greater our capacity to make conscious choices in life. The less self-awareness we have, the less we will cultivate our growth mindset and explore our full potential.

The vertical axis divides our world into the conscious, values-based, self-regulated choices on the right and the quick-fix, numbing, conditioned, fear-based responses on the left.

The Growth Matrix can be summarised as follows:

- Quadrant 1 in the lower right represents our growth values, which pull us in the direction of our conscious intentions. Rather than assumed values that have been handed down to us from parents and society, this is where we consciously choose values that will enable us to vertically grow to become more conscious, balanced human beings, leaders and organisations that make the world a better place.

- Quadrant 2 in the upper right represents the conscious, committed actions we take to move towards quadrant 1 and change our unconscious behaviour. From a leadership perspective, this is what we commit to and practise to ensure we actually walk the talk we formulated in Quadrant 1.

- Quadrant 3 in the upper left represents the behaviour that flows from habit and our unconscious fears, attachments and assumptions. This is what we are doing when not moving towards the right side of the matrix. These are the habitual coping mechanisms that provide us with short-term relief from our discomfort or quick rewards, while usually damaging our relationships, diminishing our influence, wasting our time and energy, and preventing us from achieving our intent and commitments in quadrants 1 and 2.

The ‘Deny & Numb’ and ‘Justify & Blame’ tabs in quadrant 3 are important to understand, as they keep us locked into quadrant 3 behaviours and prevent us from exploring quadrant 4’s unconscious drivers. The numbness and denial element — what we call the ‘first line of defence’ against our shadow — literally enables us to not fully notice or take accountability for our unconscious ‘moving-away’ behaviours. The justification and blame element is what we call the ‘second line of defence’ against the shadow. This occurs when we break through the first line of defence (numbness and denial) and acknowledge quadrant 3 behaviours, but very quickly justify them or blame others. In doing so, we fail to take the next step into understanding our deeper fears, attachments and assumptions in quadrant 4, while continuing to engage in our quadrant 3 behaviours.

- Quadrant 4 in the lower left represents our unconscious fears, attachments and assumptions (our conditioning) that drive our moving away behaviours and ensure resistance to our commitment in quadrant 2. This is the realm of our internal mental and emotional baggage that holds us back from achieving our full potential. We see and take accountability for our quadrant 3 behaviours. This is what Carl Jung called ‘shadow work’, as it describes the exploration of our unconscious behaviour and its drivers, our ego or the unknown and darker side of our personality that we wish to move away from. This part of ourselves was often conditioned in our earlier, formative years or through traumas or difficult experiences.

The tab labelled ‘Inner Psychological Safety and Distress Tolerance’ in quadrant 4 represents the two core skills we need to explore our shadow. Without them, our inner work is too confronting and we fall prey to the first and second lines of defence. Among other factors, inner psychological safety refers to self-compassion and curiosity. Distress tolerance refers to our ability to accept and handle difficult emotions without running from them through defence or numbing mechanisms. The more distress tolerance we cultivate, the more we are able to stay curious and growth-minded in the face of emotional discomfort and pain.

- Self-awareness and self-regulation are placed in the middle of the matrix, as without self-awareness and the ability to consciously regulate our behaviour, we cannot deliberately live a values-based life, nor can we learn to see, accept and compassionately take accountability for the shadow that moves us away from our best intentions.